This is the second half of my recollections of Noguchi. For the first half, go here.

After dropping my wife Fuki off at the Army hospital maternity ward in Sagamihara, I took the shinkansen “Bullet Train” from Tokyo to Okayama, changing trains there for Uno to board the ferry across the inland sea to Takamatsu.

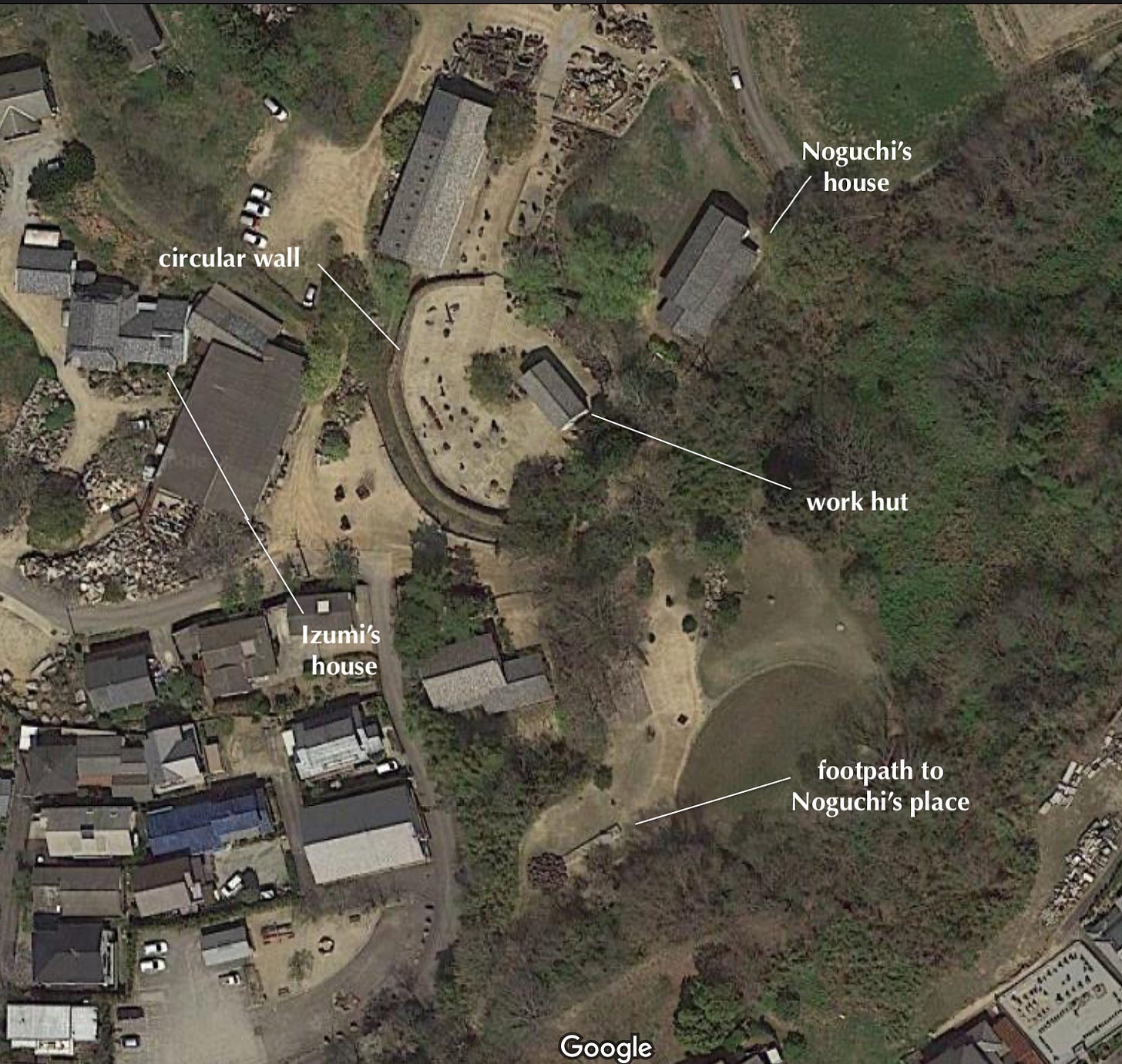

From Takamatsu station, the bus took about ten minutes, and the driver seemed to know where to drop me off for the five-minute walk up a dusty lane to Noguchi’s place. This path passed a low open shack with a wide corrugated metal roof. Under the roof, a worker who appeared to be standing waist high in a trench was noisily ministering to an enormous black stone loop.

Leaving my things with Yuriko, the same housekeeper who had served us tea at the inn in Tokyo, I continued up to the work hut. Noguchi himself had only arrived the day before. Pointing to the great circular wall that surrounded the work yard, he quipped, “Piled high by the grannies of the neighborhood.”

Noguchi explained that the black granite sculpture I had noticed in the low shack was to be lifted out by crane the next morning and set upright here in the circular yard to be photographed. “I can’t afford to transport large sculptures overseas. I need to set it up to take photographs, so I can go around and peddle it to museums.” After giving me a chance to look around, Noguchi took me along to seek out his assistant Masatoshi Izumi at home.

Izumi’s house was quite unusual; it seemed to be a house within a house. The inner two-story house appeared to be of traditional design, but the outer house had high windows admitting plenty of light and a surrounding “mud room” with a smooth dirt floor. Izumi was out, but as we stood in this mud room Noguchi began to tease Mrs. Izumi about the remarkable long black stone counter with a deep sink carved at one end, all one piece. “What a fancy new sink you have!” The sink, standing by the entrance on the dirt floor, truly was an artwork in its own right.

Aji-cho is known throughout Japan for its granite, and Izumi descended from a long line of stonecutters there, makers of funerary monuments and stone lanterns. As the afternoon continued, Noguchi told me, “I really couldn’t do anything here without Izumi. At first, it was difficult to persuade him to leave the traditional family business and devote himself to my work, but he understands what I want implicitly. And he’s done well by his decision.”

In the evening Noguchi suggested I bathe, a customary gesture of hospitality in Japan. “There’s a yukata for you, but put on your underpants afterwards.” Yukata, a sort of summer weight kimono, can be short. I laughed. “Yes, I’ve made that mistake before.”

The shower was oddly dark, steamy, modern, with a stylish flooring of smooth gravel shaped like go pieces.

The house was a two-hundred-year-old traditional house that had been dismantled, transported, and rebuilt on this site. It had an impressive timber frame of robust proportions, elegant, spare, and sparsely furnished. Noguchi explained to me that he was highly sensitive, that he absorbed sensations like a sponge, and that he required his surroundings to be just so. The guest room was up a stark flight of open wood stairs, and off a high-ceilinged upstairs hall. All the upstairs ceilings disappeared into the darkness of the roof structure. The hall at the top of the stairs contained a low table on which sat a scale model of a plaza with tiny elements barely an inch tall, exquisitely fashioned in plasticine; I’d seen the identical arrangement of stones mocked up full-scale in the yard. The guest room itself had a smallish low window at the far end, tatami mats, and a futon beneath a single long helical paper lamp that hung from above.

The next morning, I woke up late, so late in fact that I missed the entire operation with the crane! I had slept so soundly, I never heard a thing. Yuriko regarded me with pity as she offered breakfast in the kitchen. Noguchi looked at me askance when I arrived at the yard. In truth, while he was already 70 and I was just 22, he walked faster than I did, headlong and vigorous with intention.

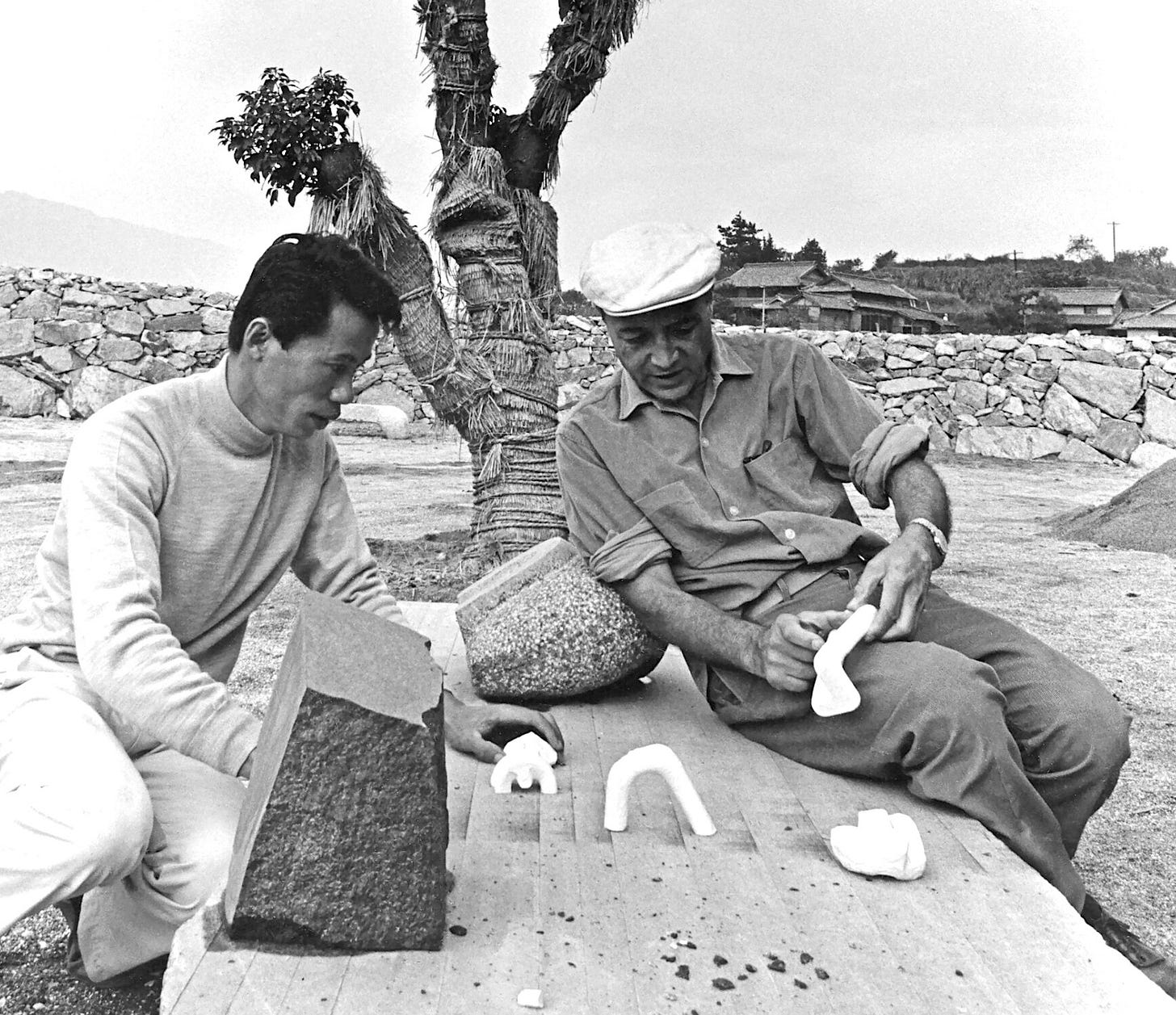

Later on, Noguchi showed me the garden behind his house where a long thin marble sculpture twisted across the ground. He told me of his time with Brancusi (while on a Guggenheim fellowship in Paris when he was 22 years old, he had apprenticed with Brancusi, who taught him to carve marble), but said that actually his work was the opposite of Brancusi’s. Whereas Brancusi carved to uncover the essential resistant form within, his—Noguchi’s—approach was more plastic, fluidly shaping the stone to conform to his will.

The day was clouding over and getting rainy, so we retired inside. Later in the afternoon he was expecting Izumi to drop by, so for the time being he suggested we play Othello, a board game resembling the game of go, but simpler and on a smaller field. I was somewhat nervous playing the great man, and didn’t really know how to play, although he explained a bit as we went along, but eventually he became impatient with my dumb moves and turned his side over to Yuriko. He looked astounded when it turned out I beat Yuriko, and she and I both laughed, as the implication was that either Yuriko was letting me win, or I had been letting Noguchi win, or Noguchi was actually forfeiting a bad position that I hadn’t comprehended yet.

Soon, Izumi arrived along with a younger fellow who turned out to be a stone scout. I had brought a couple of large bottles of saké; tied together with string, these were a customary gift for a guest to bring on a journey. We opened a bottle, and Noguchi stood to take a sip. “Karai!” he exclaimed, while holding up his cup. Karai means “dry,” and is almost a way of saying “terrible” when it comes to saké. “Have you ever tasted this?” I admitted I hadn’t. I didn’t really know much about saké; I had simply brought it because it was from the local brewery near my house. Everyone laughed.

Soon the conversation got very animated. I couldn’t follow all that was being said. At one point, Noguchi turned to me and said, “Around here we are all stone crazy!” He explained that this younger fellow had discovered a batch of dark basalt boulders that had been submerged in the mud of a river for ages such that they were encrusted with a patina of red iron oxide, and was urging Izumi and Noguchi to get them. They were all extremely excited.

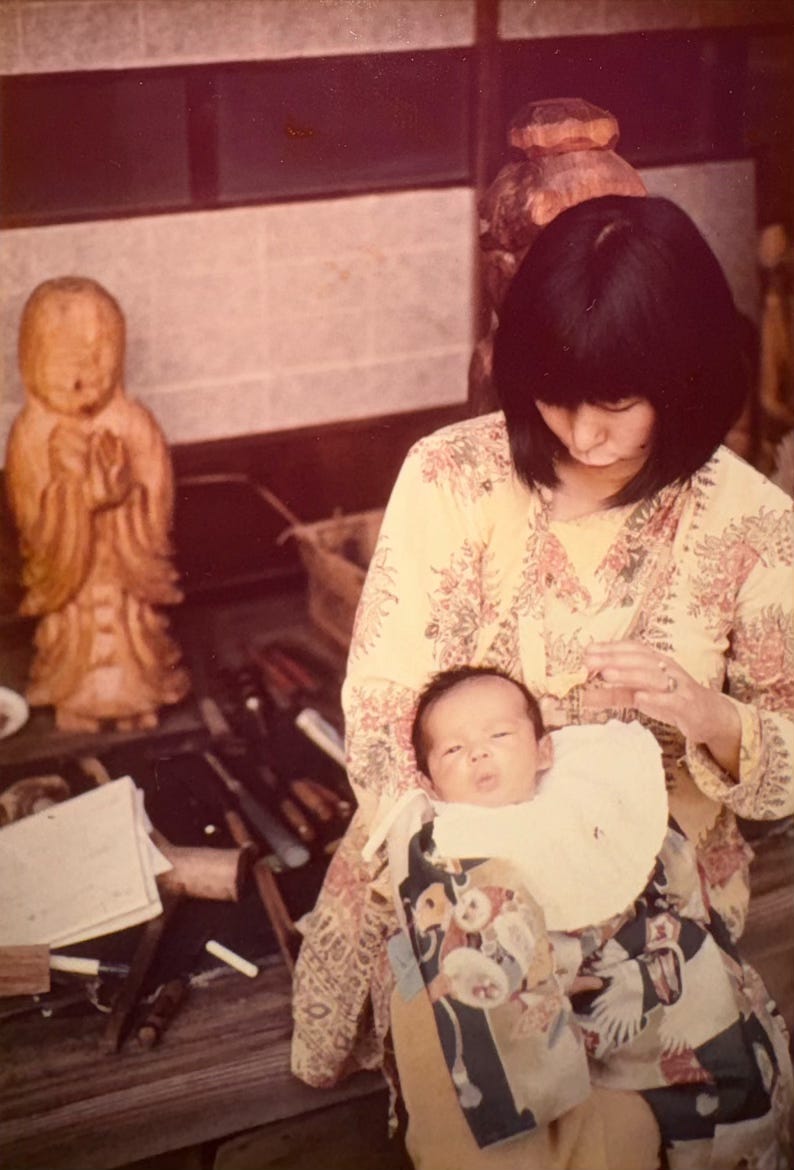

As Izumi was about to leave, Noguchi asked me whether I had photographs of my work to show, but I had to admit that I had none (at that time I didn’t even have a camera), that I had brought some carvings in my station wagon when we first met in Tokyo, but hadn’t brought them in at the time. When I explained that I was carving butsuzo (Buddha sculptures) in wood, Izumi brightened and said we should visit the local temple to view the statues there. Noguchi frowned. “He’s leaving tomorrow, and anyway we haven’t the time.”

That evening Noguchi and I sat together on the ledge of the tatami in the living room with a large stone sculpture before us. It was time for me to make my pitch. What about coming there to apprentice? Noguchi said that carving granite was “slavery,” that he had studied stone carving in marble—much better. I said, but you are doing granite here. He shrugged; there was no real rejoinder to that. (At some point I noticed that he was looking at my foot, and then I looked too and realized that I was unconsciously probing a cavity on the side of the base of his sculpture with my big toe. Neither of us mentioned the fact, strange as it was.) He mentioned that they had had trouble with a hanger-on in the past. I said I wanted none of that, I wanted to learn and work. He explained that he came and went, and that it was really up to Izumi, this was Izumi’s operation. He pointed out that language might be a problem. I explained that my wife was Japanese, in fact she was back home having our baby induced that weekend (the first I’d spoken of that), and that she was good at communicating and we could probably figure out a way. He said, then you should bring the matter to Izumi.

I left first thing the next morning, and in farewell Noguchi intoned, “You will go far.”

On the trip home I was full of hope. Despite some blunders, it seemed to have gone well and I thought there were good possibilities. I could tell that Izumi and I would get along well. There was a way.

When I got to the hospital, I was surprised to learn that Dr. Fleet had not induced the birth of our baby. X-rays of the fetus’s femur showed that the time was not yet ripe.

Thus, it was a couple of weeks later that our son Lao was born, an event necessitating a helicopter ride to the far-off naval hospital at Yokosuka.

A couple days after Lao’s omiyamairi, a representative of the Red Cross appeared at my desk to announce a medical emergency. My mother was diagnosed with leukemia and I was required in America immediately! A cargo plane was flying tomorrow. I left Japan on 24 hours’ notice.

Once I got home, I realized the best thing I could do for my mom was stick around and go back to college. And so, all my plans to apprentice in Japan came to a sudden end.

Thinking about these memories today, two things stand out in my mind.

First of all, I am struck by how strongly the illness, and soon death, of my mother altered the course of my life, bringing me back to college in America and then returning me to my family home for what ended up being another twenty years.

Furthermore, I am touched by the kindness and patience Isamu Noguchi showed me by inviting me to visit his studio to see how he worked, and by how much he could impart to me about being a sculptor in even such a few short days, often inspiring me since then to redouble my efforts to accomplish things worthwhile.

As of okonomiyaki: was it Kantō-style? Kansai-style of Ōsaka, Hiroshima or Kyūshu is even more tasty, for what I am concerned. Anyway, long time ago …

This finally inspired me to try out your okonomiyaki recipe. Came out fabulous, very tasty, though I used red cabbage and threw in some radish leaves...